Your Brain on Feedback: Why People Resist Correction and How to Fix It

The moment arrives. You call your team together. You’ve reviewed the project, seen the gaps, and you’re ready to give feedback. You speak clearly: “Here’s what we did well. Here’s where the work needs a shift.” You invite questions. A few nod. Some faces tighten. A quiet, almost imperceptible, tension ripples in the room.

Later you wonder: Why didn’t they respond the way you hoped? Why did some lean in, while others withdrew? Why, despite your best intention to support growth, did the feedback feel like a setback?

Moments like these reveal something deeper: Feedback is never just information. It is emotion, identity, and instinct colliding in real time. The brain interprets correction as both an opportunity and a threat, shaping whether people rise, resist, or retreat.

The Scene

A professional invests weeks into a major project, researching, refining, and polishing every detail. When feedback arrives, it’s clear and actionable: a few elements need reworking, a section should flow differently, some visuals could be simplified. The critique is fair, even constructive.

Still, a wave of defensiveness rises. Thoughts race. Did I miss something? Did I fall short?

What happens in that moment is profoundly human. Feedback engages both logic and emotion, shaping how people interpret and respond to information. The brain doesn’t just process “Here’s what to change.” It also asks deeper questions: Am I competent? Do I belong? Am I safe?

Why People Resist Feedback: The Brain’s Perspective

Threat vs. Growth Signals

The human brain evolved in environments where being ostracised or deemed incompetent often meant danger. Consequentially neural systems that monitor for threats remain highly sensitive. Research shows that when learners receive confirmatory feedback, simply “You are wrong” or “This is incorrect” without guidance, the amygdala (fear response) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (conflict/monitoring) activate more strongly. In contrast, informative feedback, “Here’s what you did; here’s how to adjust,” engages the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, enabling cognitive control and regulation of negative emotion.

In practical terms this means when someone hears correction in a vague or undirected way, the brain may prioritize threat detection (“I’m wrong / I’m judged”) instead of learning. Emotional arousal consumes cognitive resources, reducing the capacity to process the what and the how.

Identity & Belonging

Feedback often touches our implicit self-story: “I’m a capable contributor,” “I belong on this team,” “I’ve been performing.” When new information suggests otherwise, the brain experiences identity dissonance. That dissonance triggers avoidance, rationalisation, or silence. The learner might nod outwardly, but inwardly is busy self-protecting.

Cognitive Load & Timing

Another layer: the learner’s cognitive bandwidth. Corrective feedback arrives most usefully when the brain has enough space to integrate it. A study of older adults found that delayed feedback sometimes improved learning because it allowed the memory networks (medial temporal lobe) to engage more effectively than immediate feedback dependent on striatal circuits. If feedback comes when the learner is overloaded, distracted, or already fatigued, it can land poorly.

Motivational Factors

Feedback carries emotional weight as well as insight. People interpret it through both feeling and reasoning, allowing reflection to lead to growth. One recent study found that individuals with low confidence are more likely to seek corrective feedback and actually benefit from it. On the flip side, feedback delivered in a manner that threatens self-efficacy can reduce motivation and engagement.

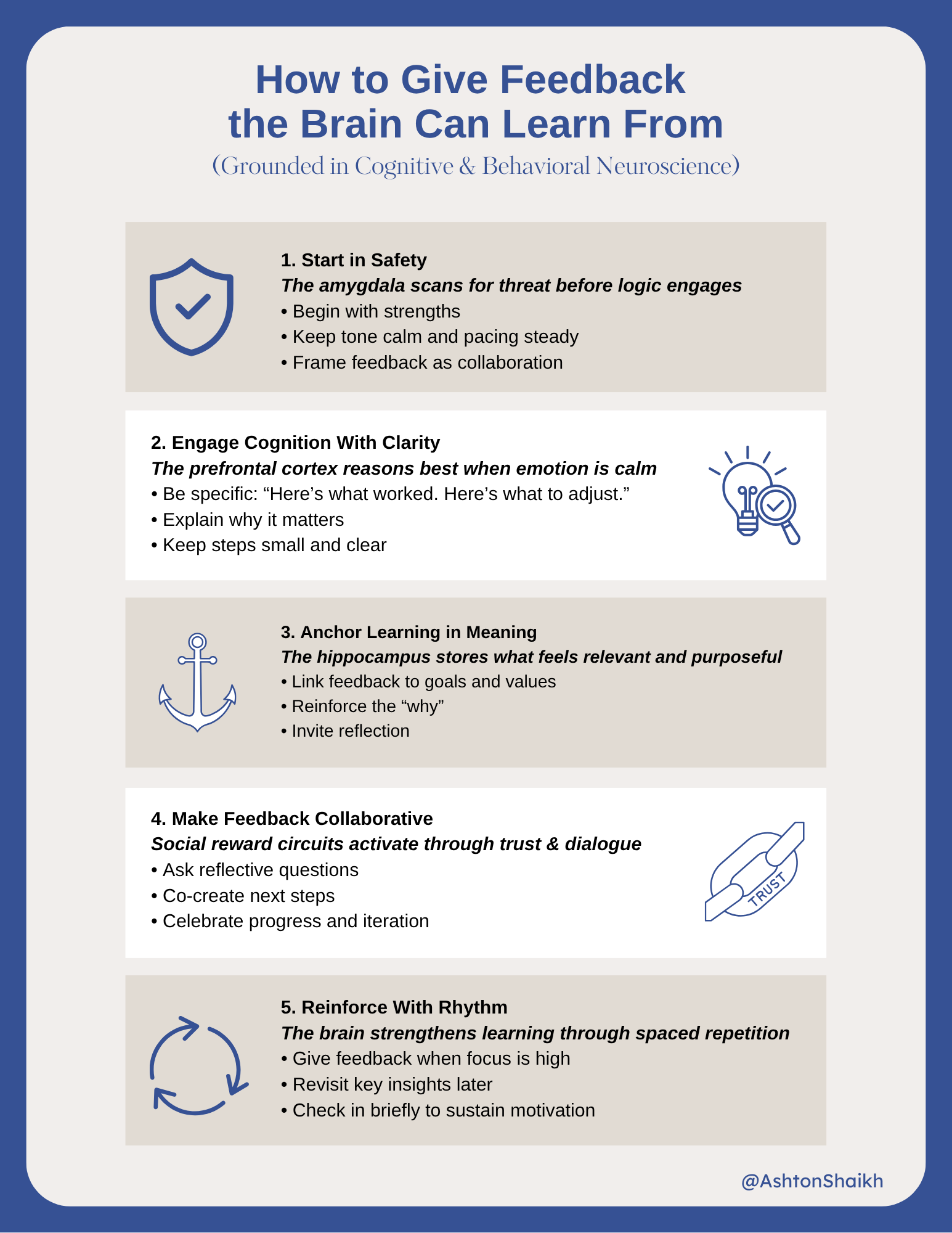

How to Make Feedback Work: Brain-Smart Strategies

With the science clear, what actionable steps can you take to redesign how feedback lands, is received, and leads to change?

1. Lead with the Learner’s Story

Before diving into “Here’s what to fix,” open with: “Here’s what you achieved.” Acknowledge the effort, the progress, the intent. This primes the brain for safety, reduces threat response, and opens cognitive space for growth. Framing feedback inside a narrative of learning (“Here’s where you are on your journey”) helps the learner feel part of a story of improvement rather than a verdict.

2. Make Feedback Informative and Growth-Focused

The 2015 imaging study clearly distinguished the neural impact of different types of feedback. When feedback simply signals “wrong” it triggers emotional circuits. When it provides task-relevant information and guidance it allows cognitive control systems to regulate emotion and engage change. So structure feedback like this:

Briefly state the performance gap.

Then show why the gap matters (context).

Then outline how to bridge it (specific, actionable steps).

Keep the “why/how” front and center.

3. Create a Reflective Dialogue Rather than a Monologue

People resist correction when they feel judged. Invite the learner to reflect: “What were you trying to achieve? What might you do differently? What supports do you need?” This helps shift from passive recipient to active agent. From the neuroscience side, active engagement (rather than passive receipt) enhances encoding of new information and reduces threat-based responses.

4. Frame Feedback as Identity-Aligned, Forward-Looking

When feedback is aligned with the learner’s identity (“You are someone who continuously grows and adapts”), it reduces resistance. Try: “You’ve shown you can iterate. This next version will show that in a stronger way.” The brain hears: This feedback is part of you improving, not you failing.

5. Pay Attention to Timing and Cognitive Load

Feedback delivered when the learner is cognitively fresh, emotionally steady, and mentally available will land much better. If someone has just battled back-to-back meetings or is about to jump into a project, feedback may feel like another hit instead of an opportunity. When possible, schedule feedback when attention is available and fatigue low.

6. Support Multiple Feedback Loops

Learning from feedback is not a one-off event. The hippocampus, striatum and prefrontal networks all play roles in feedback learning; research shows that memory interference (e.g., multiple simultaneous tasks) can degrade feedback-based learning accuracy. Building iterations helps the brain process, reflect, adjust, and reinforce.

7. Encourage Feedback-Seeking Behaviour

Create an environment where learners ask for feedback rather than only receive it. The neuroscience of feedback-seeking shows that when people proactively engage with feedback, their learning outcomes improve. A culture of curiosity reduces the threat-valence of correction.

Back to the Scene: How the Story Changed

With a renewed mindset, the next feedback meeting unfolds differently. The manager begins: “You built a strong foundation in the pilot. Let’s expand on that momentum. Here are three areas we can strengthen together.”

Instead of reacting defensively, the professional leans in with curiosity: “What would an ideal outcome look like? What signals will tell us we’re moving the needle?”

The conversation turns collaborative. Together, they clarify goals, define next steps, and align on impact. The meeting ends with energy, clarity, and shared ownership, growth replacing guardrails, partnership replacing pressure.

The Bottom Line

Feedback creates impact when aligned with how the brain works: seeking safety, identity coherence, balance, and purpose. When we redesign feedback through that neuroscience lens, we transform correction into connection. We turn resistance into readiness.

When giving feedback, the goal extends beyond pointing out areas for change. The exchange becomes an invitation into a story of growth, one where the brain is engaged to learn, adapt, and thrive.

Let your next conversation start not just with “Here’s what went wrong,” but with “Here’s where you are next, and how we’ll get there together.”