What the Brain Reveals About eLearning Myths (and How to Move Beyond Them)

In every organization, there’s a silent moment between clicking “Start” and deciding whether to stay engaged. For one learner, it’s curiosity that leans them forward. For another, it’s fatigue that makes them glance at the clock. That moment highlights what the best designers know: Platforms deliver content, but the brain creates understanding.

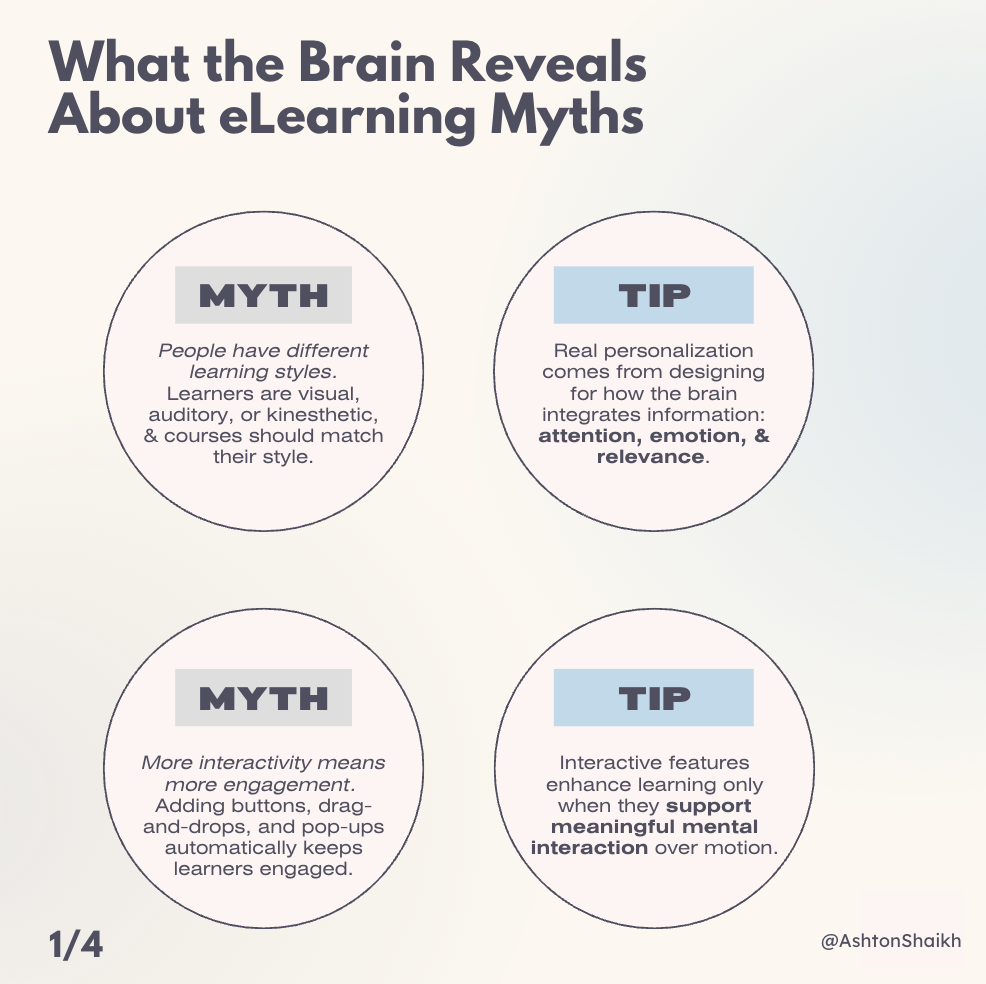

We’ve been told stories about what makes learning work. Visual learners need more images. Interactive courses mean engaged learners. Microlearning fixes attention. These ideas sound intuitive; however, neuroscience tells a different, more hopeful story, one that honors how the brain actually learns, connects, and remembers.

1. Capturing Attention: The Myth of Learning Styles

Imagine a learner opening a new compliance module. A bright banner flashes: “Choose your learning path: visual, auditory, or kinesthetic.” They pick one, relieved to finally have something that feels personal. Yet twenty minutes later, their mind drifts.

For decades, educators and designers have been told that matching instruction to a preferred style enhances learning. The theory promised personalization, but studies across cognitive neuroscience haven’t found evidence to support it. Research by Pashler et al. (2008) and later Rogowsky et al. (2020) shows no performance improvement when instruction matches a reported style.

The reason is beautifully simple: The brain learns best through integration. Learning ignites through multiple systems working together: sensory, emotional, cognitive, and social (Immordino-Yang, 2019). Visuals matter, but only when they connect to meaning. Words matter, but only when they build context. What we call “learning styles” are often just preferences for entry points rather than pathways to mastery.

The real key to attention lies in curiosity. Dopamine, the neurotransmitter tied to motivation, rises when the brain detects something new but relevant (Bromberg-Martin & Hikosaka, 2011). Curiosity is the ignition that tells the learner: This matters to me.

2. Informing Learners of Objectives: Why Meaning Beats Memorization

The human brain craves purpose. When people understand why they’re learning something, they anchor it in the prefrontal cortex, or the seat of planning and reasoning. Without meaning, facts slip through working memory like sand through fingers.

Many eLearning modules begin with long lists of objectives written from the designer’s perspective: “Learners will identify, explain, demonstrate…” But clarity isn’t the same as connection. Neuroscience reminds us that emotion and cognition work in tandem (Damasio, 2018).

A more powerful opening tells a story that answers the question every learner’s brain quietly asks: Why should I care? When we replace generic objectives with real-world stakes, like someone’s safety, time, or success, attention turns into engagement.

3. Stimulating Recall: The Myth That Information Equals Learning

A new hire scrolls through a module filled with facts, policies, and bullet points. They click “Next,” pass the quiz, and remember almost nothing the next morning. Information is not learning. Memory relies on retrieval, which is the brain’s act of pulling information forward and applying it in context. Working memory can hold only a handful of items at once, and cognitive overload disrupts recall.

Designing for recall means spacing information, connecting it to what learners already know, and allowing mistakes to guide discovery. Instead of flooding the screen, the designer might ask: “What would you do first if a team member ignored PPE protocol?” The learner must think, predict, and compare. This act of retrieval strengthens neural pathways far more effectively than passive review.

4. Presenting Content: The Myth That More Interactivity Means More Learning

It’s easy to believe that the more clicks, the more engagement. Designers often add drag-and-drops, pop-ups, and hover reveals in the name of interactivity. But cognitive research shows that engagement is about meaning.

When learners pause to interpret complex navigation or decoration, they use valuable working-memory resources for design rather than learning (Soderstrom & Bjork, 2015). The goal is to focus the brain on understanding, guiding attention toward meaning and mastery.

Imagine a module that begins with a realistic decision: “You arrive at a worksite and notice a safety risk. What’s your first step?” Each choice unfolds a short narrative. Learners stay engaged not because of visual novelty, but because their decisions matter. Relevance truly transforms interactivity from motion into cognition.

5. Providing Guidance: How Feedback Builds Understanding Rather Than Testing It

Traditional eLearning feedback ends with two words: “Correct” or “Incorrect.” Those words satisfy grading systems but not the brain. The brain learns through prediction and feedback loops, a process tied to dopamine regulation (Schultz, 2016). When feedback reduces uncertainty and provides explanation, the learner experiences a small reward response that encourages further effort.

Imagine a compliance scenario where the learner chooses a low-risk path. Instead of “Incorrect,” the module responds: “This response could work in low-risk situations. In this case, escalation is needed because time is critical.”

The learner receives feedback that refines understanding rather than triggers defense. This clarity keeps curiosity alive and reinforces accurate mental models. Guidance also means adjusting support. Adaptive scaffolding, as Plass et al. (2019) found, allows learners to access help when needed and remove it when confident, fostering metacognitive growth and self-trust.

6. Eliciting Performance: The Myth That Shorter Is Always Better

Microlearning became the buzzword of the last decade. The idea that short bursts equal better focus has truth behind it, but brevity alone isn’t the solution. A five-minute video crammed with ten new ideas still overwhelms the brain.

The real goal is cognitive coherence: structuring learning into digestible, meaningful chunks that align with how the hippocampus organizes memory. When a course invites learners to act, like to make decisions, record reflections, or demonstrate a process, the duration becomes secondary to depth. A simple prompt like, “Record a 30-second reflection describing how you applied this policy today,” transforms passive consumption into embodied learning. The brain stores it as lived experience, transforming knowledge into understanding.

7. Providing Feedback: The Myth That Speed Equals Quality

Designers often celebrate instant feedback. The moment a learner answers, the screen reveals right or wrong. But reflection needs space. Neuroscientist Mary Helen Immordino-Yang (2019) found that emotional and reflective processing require downtime for the default mode network to integrate learning.

Immediate correction can satisfy the system but short-circuit the synthesis. When learners have a moment to pause, revisit a concept, or compare their reasoning, feedback shifts from transactional to transformational. Feedback should feel like a mirror that reflects growth and possibility, guiding learners toward deeper understanding.

8. Assessing Performance: The Myth That Testing Proves Learning

A multiple-choice test might measure recall, but it rarely measures readiness. The brain encodes information contextually: what we remember depends on where and how we learned it. When assessment divorces knowledge from context, transfer suffers.

A more accurate picture emerges when assessments reflect real decisions. Scenario-based assessments simulate judgment calls, emotion, and time pressure, allowing learners to practice applying knowledge in meaningful, authentic ways. Soderstrom and Bjork (2015) describe this as “desirable difficulty”: the productive struggle that strengthens retention and flexibility. As learners navigate authentic choices, assessments become opportunities for insight and growth. They begin to see themselves as capable thinkers and active participants in their own learning journey.

9. Enhancing Retention and Transfer: The Myth That Learning Ends at “Complete”

A learner finishes the course, earns a certificate, and moves on. But the forgetting curve begins within hours. Without reinforcement, neural connections weaken. True learning design extends beyond the module. Spaced repetition, reflection prompts, and job aids reactivate neural pathways and build long-term memory (Carew & Murr, 2019). Organizations that treat learning as a living system, something revisited, practiced, and celebrated, see measurable gains in performance and confidence.

10. Where to Begin

The myths that shaped eLearning grew out of a genuine desire to reach every learner. Neuroscience now provides a clearer map, one that turns intention into insight and assumption into awareness.

Here’s where to start:

1. Begin with curiosity and connection.

Ask learners what helps their brains engage and focus, exploring their preferences and strategies instead of assigning fixed labels.

2. Write objectives as purpose statements.

Frame the “why” in human terms: “This process protects your safety and your team’s success.”

3. Design for recall and lasting understanding.

Space information over time, connect it to experience, and invite reflection through thoughtful questions.

4. Simplify the screen.

Every pixel should serve cognition. Consistent layouts calm the brain and preserve attention.

5. Make feedback informative and kind.

Replace judgment with guidance that explains reasoning and reinforces confidence.

6. Assess through application.

Use real-world scenarios, short reflections, or simulations instead of isolated quizzes.

7. Extend learning beyond the module.

Drip content, schedule reminders, and celebrate application in the field.

Each step moves design closer to how the brain naturally learns: through emotion, relevance, repetition, and reflection.

Concluding Thoughts

The brain’s design for learning is breathtakingly generous. It adapts, rewires, and grows through experience, connection, and care. The most effective eLearning earns attention by aligning with the brain’s natural processes, engaging curiosity, emotion, and meaning to build lasting understanding.

When we trade myths for mechanisms and design for belonging, clarity, and curiosity, learning becomes more than a task. It reflects what we believe about people and their capacity to think, to grow, and to change.