Know Your Guests: The Secret Ingredient to Great Learning (and Great Thanksgiving Dinners)

The Table and the Lesson

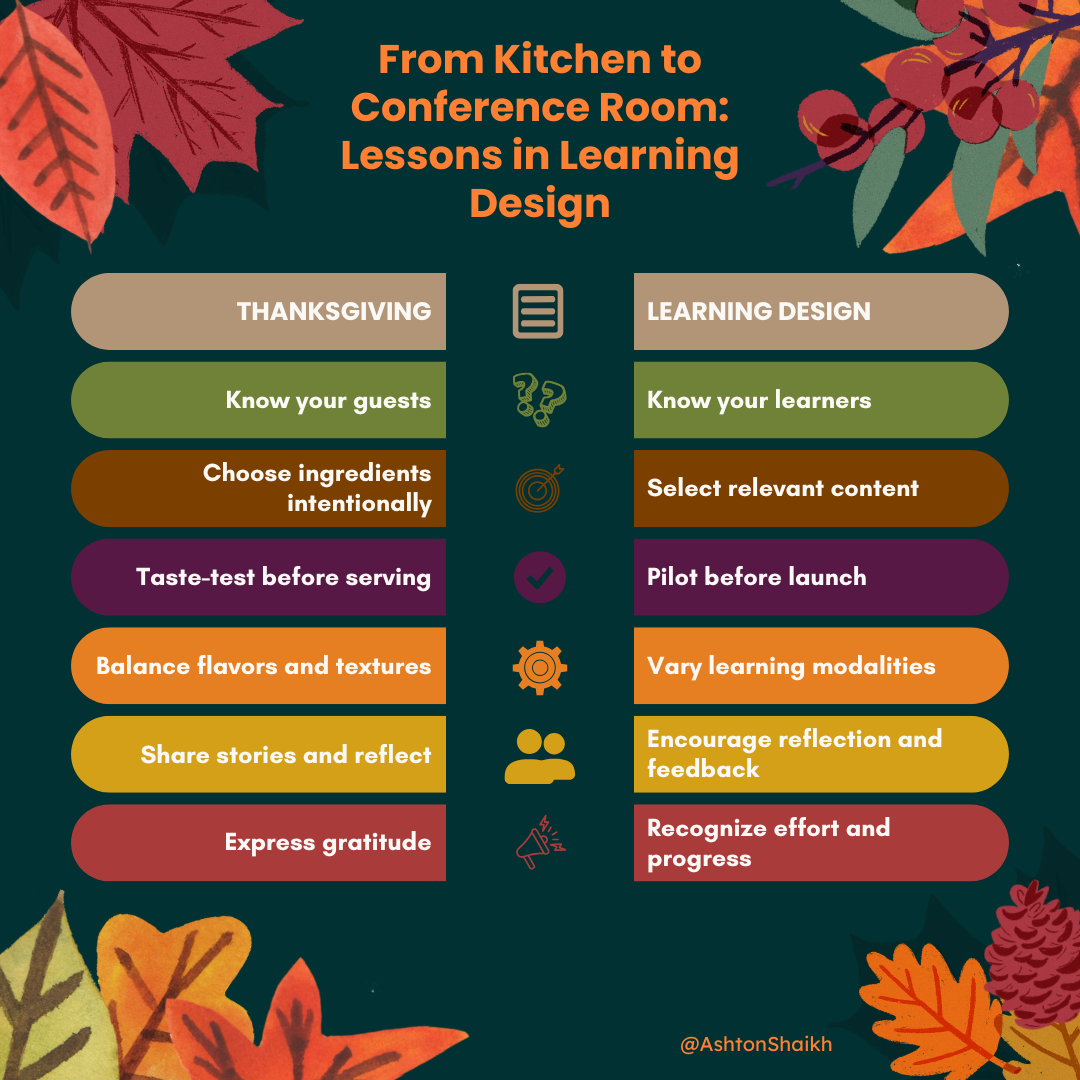

The kitchen hums with quiet choreography. A pan sizzles, voices mingle, and the scent of sage and butter fills the air. The table is set with care, every detail designed to make guests feel welcome. A guest with dairy sensitivity eyes the mashed potatoes. Another laughs over a memory of last year’s burnt rolls. Someone reaches for cranberry sauce from a can, another for the homemade version. There’s no universal recipe for this dinner, only people with preferences, stories, and needs.

Designing learning experiences follows the same rhythm. Success depends less on how elaborate the recipe is and more on whether the designer truly knows the people being served. The difference between a meal that nourishes and a plate that overwhelms often comes down to preparation grounded in empathy. Every engaging learning experience, like every memorable holiday meal, begins long before the first slide or the first bite.

The Brain’s Appetite for Relevance

Neuroscience shows that attention, emotion, and cognition work in partnership. The prefrontal cortex, which guides reasoning and planning, relies on input from the limbic system to determine what matters enough to remember (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2016). In the same way that a cook chooses ingredients based on the guests at the table, instructional designers must understand learners early to determine what will hold attention and build understanding. The brain learns best when information connects to identity and purpose (Carew & Magsamen, 2020). Design without context feels like serving a beautiful dish that no one can eat.

Imagine a compliance module launched to hundreds of employees. The goals are clear, the interface polished, and yet completion data shows rushed clicks, low recall, and survey comments like, “I just wanted to get through it.” That response mirrors the polite but strained smile of a dinner guest faced with dry turkey: technically correct yet emotionally off. The issue rarely lies in the content itself. The disconnect arises because relevance, the neural spark that binds emotion to cognition, never ignited.

Emotion, Belonging, and the Learning Brain

Every brain entering a classroom, webinar, or course carries more than prior knowledge. Learners bring histories, expectations, and unspoken concerns about belonging. A 2021 study from the Journal of Educational Psychology found that students who perceived their learning environments as emotionally safe demonstrated significantly higher cognitive flexibility and transfer of learning (Zeidner et al., 2021). Safety precedes synthesis. Emotion serves as the gatekeeper for cognition. Before the brain allocates resources to memory or reasoning, the amygdala scans the environment for threat or meaning. A learning experience that feels disconnected from the learner’s reality can quietly activate this threat response, reducing available working memory. When learners feel unseen, they disengage not because of disinterest but because their neural systems are prioritizing safety over exploration.

Understanding learners early provides the context needed to activate curiosity instead of caution. A conversation, a survey, or a brief empathy interview can reveal what no dataset can: the lived experience shaping how people perceive and absorb information. Design grounded in curiosity communicates care. That sense of care creates the emotional coherence needed for retention and reflection.

How: Designing Like a Thoughtful Host

1. Start With Discovery Before Assumption

The best hosts don’t assume; they ask. “Any allergies?” “What’s your favorite side?” “Do you like your stuffing crispy or soft?” In learning, those same questions translate to curiosity about learners’ backgrounds, barriers, and motivations. Before drafting outcomes, designers can explore:

What does success look like for this audience?

What pressures, incentives, or values shape their decisions?

What emotional state will they bring into the learning environment?

Even brief conversations can reveal insights that shape cognitive design choices. Research on retrieval-based learning by Soderstrom and Bjork (2015) shows that prior knowledge directly influences retention; new information must connect to familiar patterns to transfer effectively. Discovery creates those bridges before instruction begins.

2. Define Purpose as the Core Ingredient

Purpose transforms information into meaning. A strong objective clarifies what to do and explains why it matters. Instead of “Learners will identify three safety procedures,” a designer might frame, “You’ll recognize how each safety protocol protects your teammates and ensures everyone returns home safely.” The phrasing activates empathy and self-relevance. The learner’s brain interprets the material not as a checklist but as part of their professional identity. According to Damasio (2021), meaning-making integrates bodily states, emotion, and reasoning into what he calls “feeling of knowing,” or the sense that understanding is both cognitive and personal. Purpose creates this neurological bridge.

3. Build Variety Into Experience

A Thanksgiving table succeeds because it celebrates difference: crunchy, soft, spicy, sweet. No single dish carries the whole meal. Universal Design for Learning echoes this principle. Learning becomes inclusive when multiple pathways exist for engagement, representation, and expression. In practice, that could look like:

offering both visual and verbal ways to explore concepts

providing reflection prompts alongside interactive challenges

allowing learners to choose between a story, a simulation, or a scenario

Choice activates dopamine, the brain’s reward signal for autonomy (Bromberg-Martin & Hikosaka, 2011). When people feel agency, motivation rises and cognitive load decreases.

4. Taste-Test Early and Often

No skilled cook serves a dish without sampling it first. Likewise, designers should preview early drafts of learning experiences with a small group of representative users. A brief pilot reveals more than mistakes, highlighting where emotion, pacing, and clarity can be refined. Learning analytics can show how long users spend on a slide or where they drop off, but direct observation or interview reveals why. That qualitative insight is the neural equivalent of tasting the seasoning before serving. Iteration ensures alignment between intention and perception, one of the defining factors of learning effectiveness (Mayer, 2021).

5. Reflect, Revisit, and Reinforce

Thanksgiving doesn’t end when the plates are cleared. Stories linger, recipes evolve, and next year’s dinner improves through reflection. Learning follows the same cycle. Spaced retrieval strengthens memory by periodically reactivating neural pathways (Carew & Murr, 2019). Follow-up prompts, micro-reflections, or short scenario refreshers help the hippocampus consolidate learning into long-term recall. Reflection also reinforces meaning. When learners revisit key insights in context, like asking how a principle influenced a real decision, the brain encodes both the concept and the emotion that accompanied success.

The Hidden Neuroscience of Hospitality

Hospitality and learning share a neurological foundation: both aim to regulate emotion, reduce uncertainty, and build connection. Research on aesthetic cognition (Carew & Magsamen, 2020) describes how the brain experiences beauty and coherence when pattern and purpose align. In learning, that moment of coherence feels like clarity. The body relaxes, attention steadies, and curiosity expands. A similar phenomenon unfolds at the Thanksgiving table when conversation flows and everyone feels included. That harmony is neural, emotional, and social all at once. Understanding learners early helps designers build that same alignment inside digital and physical classrooms. By considering emotional readiness, cognitive capacity, and identity alignment, designers create experiences that feel both elegant and empathetic.

Beyond Data: Designing for Dignity

Analytics can show completion rates and test scores, but dignity shows up in how learners describe their experience afterward. “I felt seen.” “That helped me in real life.” “I felt like I belonged here.” Those phrases mark neurological integration. They signal that the brain’s reward networks, dopaminergic pathways linked to satisfaction and motivation, have been activated through relevance and belonging (Lieberman, 2019). Designing with dignity begins with understanding learners early. That understanding is the foundation of psychological safety and cognitive trust.

A Reflection for Designers and Leaders

Imagine walking into a classroom, meeting, or course where every detail felt intentional. The visuals reflect the audience’s world, the tone honors their experience, and the pacing respects their time. That sense of recognition changes behavior. People engage differently when they feel seen. Learning professionals are, in essence, hosts of human potential. Every design decision, from needs analysis to final assessment, communicates a message: You belong here. Your growth matters. The reward for that level of care is measurable. Teams learn faster, retain more, and share ideas with greater confidence (Plass et al., 2019). But beyond metrics, there is something deeply human about the process. When designers begin with curiosity instead of assumption, when they invite learners into the creative process, and when they stay humble enough to adjust based on what they discover, learning becomes an act of gratitude.

Gratitude as a Design Practice

Gratitude fuels patience, reflection, and perspective, all essential to effective learning design. In cognitive terms, gratitude activates the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which regulates positive emotion and reinforces social bonding (Kini et al., 2016). Practicing gratitude, through reflection, acknowledgment, or feedback, primes the mind for creativity and resilience. Design grounded in gratitude honors both the learner’s brain and the human behind it. It recognizes that attention is a gift, motivation is fragile, and learning is always relational. Whether preparing a meal or a module, the same principle applies: meaning is made together.

Closing Reflection: The Table as a Metaphor for Learning

A Thanksgiving table is more than a meal. It’s a map of values: generosity, belonging, curiosity, and patience. A learning experience designed with those same values invites lasting change. Every learner becomes a guest worth knowing, and every designer becomes a host of possibility. Great learning design, like great hosting, begins with three questions:

Who will be here?

What do they need most?

How can I help them feel capable and connected?

Those questions turn information into understanding and instruction into community. This season, may every designer remember that the first step in teaching is listening, and the highest form of expertise is care.