Designing with the End in Mind

How Backward Design Aligns the Brain, the Learner, and the Learning Experience

Picture a conference room on a Monday morning. A learning team is surrounded by binders, slides, and a wall of sticky notes filled with topics. Someone says, “We just need to cover all of this before the quarter ends.”

Everyone nods, but something feels off. The plan is full of content, yet no one can clearly articulate why any of it matters to the learner.

That tension, the gap between what’s taught and what’s truly learned, is where Backward Design begins.

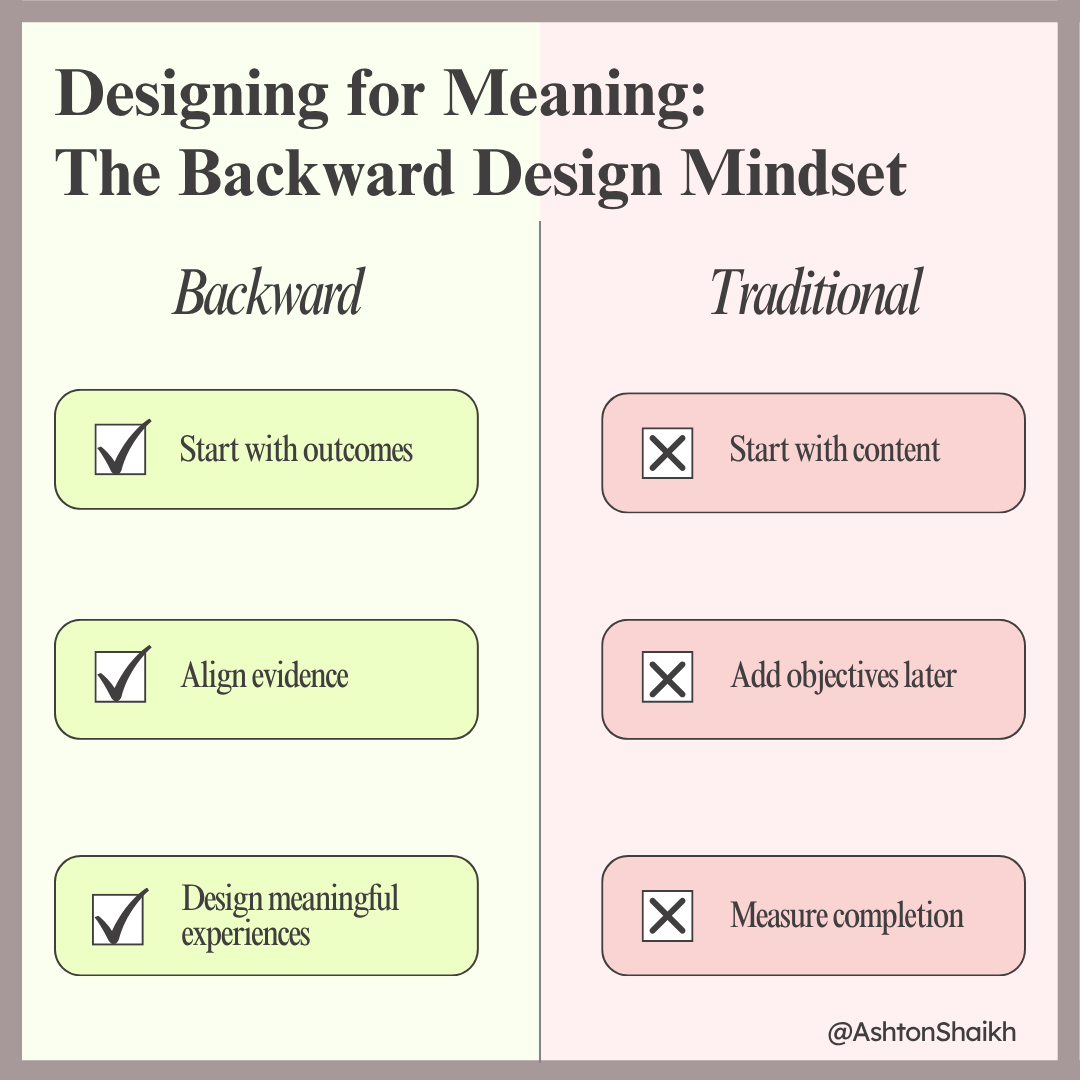

Backward Design invites us to shift the starting point. Instead of asking what content needs to be delivered, it asks what understanding needs to endure. It’s a process that transforms lesson plans, training decks, and eLearning modules into intentional journeys aligned with how the human brain builds meaning and mastery.

The Essence of Backward Design

Developed by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe in Understanding by Design (1998), the framework rests on a deceptively simple sequence:

Identify desired results: Define what learners should understand and be able to do long after the training ends.

Determine acceptable evidence: Decide how you will know that understanding has been achieved.

Plan learning experiences and instruction: Design experiences that make those outcomes inevitable.

At its core, Backward Design is a reflective thinking process that follows the brain’s natural learning path, moving from meaning to detail, and from vision to purposeful action.

Why Starting with the End Works for the Brain

Neuroscience reveals that the brain organizes new information around purpose. Every sensory input passes through the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, where it’s evaluated for relevance before being encoded into memory (Squire & Dede, Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2015). In simple terms, meaning is the filter through which memory forms.

Training that begins with a clear destination allows the brain to anchor new information to a coherent goal. In the absence of that clarity, content becomes fragmented, facts without a framework.

Predictive processing theory (Clark, 2018) deepens this understanding. The brain continuously generates predictions about what will happen next, comparing those predictions to reality and updating its internal model. When we design backward, we’re providing the brain with the same structure it naturally uses: a forecast of the goal and iterative feedback to refine it.

This is why courses built with Backward Design feel purposeful. Each piece of content becomes part of a story the brain can anticipate, test, and complete.

The Leadership Simulation

Imagine a logistics company launching a program to strengthen mid-level leadership. The initial curriculum lists ten competencies: communication, delegation, feedback, decision-making, and more. Completion rates are solid, but nothing changes in day-to-day behavior.

When the design team revisits the problem using Backward Design, they begin with one question: What would success look like three months after this program ends?

After discussion, they define the desired result: leaders whose teams solve problems independently without constant escalation.

Next comes evidence: How will we know it happened? They identify measurable signs: fewer issue escalations and higher peer-rated confidence scores.

Finally, they design the experience. Managers work through scenario-based simulations mirroring real-world challenges. Between sessions, they run small “experiments” with their teams and debrief outcomes.

The focus shifts from teaching “leadership skills” to building decision-making autonomy. In neurological terms, that shift activates the brain’s goal-directed learning systems. Every challenge offers immediate feedback that strengthens the neural connections between intent, action, and result (Davidson & McEwen, 2018).

By designing backward, the program creates meaning first, then mastery.

The Cognitive Map of Backward Design

Each stage of Backward Design aligns with a stage of learning in the brain:

1. Identify Desired Results → Purpose and Motivation

Setting a clear end goal activates dopaminergic pathways tied to intrinsic motivation (Murayama et al., 2019). When learners know why a skill matters, they experience greater engagement and persistence.

2. Determine Acceptable Evidence → Anticipation and Prediction

When learners understand what success looks like, the prefrontal cortex forms an internal model of that outcome. Every activity becomes an opportunity to test predictions, strengthening neural circuits associated with performance monitoring (Alexander & Brown, 2019).

3. Plan Learning Experiences → Practice and Consolidation

Once purpose and evidence are established, practice connects theory to experience. Myelination occurs as neural signals travel the same pathway repeatedly during applied learning (Fields, 2015). Reflection and feedback stabilize these pathways into long-term skill.

In essence, Backward Design is brain alignment by design.

Reimagining Compliance Training

A financial institution wants to improve ethical decision-making through compliance modules. Historically, their eLearning focused on rules, penalties, and quizzes. Learners clicked through quickly, remembering little.

The design team reframes it using Backward Design.

Desired Result: Employees recognize ethical dilemmas in real time and act confidently within company values.

Evidence: Case-based scenario responses and behavioral observations in quarterly reviews.

Learning Experience: Branch managers share anonymized stories of real ethical gray areas. Learners analyze these stories, make decisions, and receive feedback.

Neuroscience validates this shift. Emotional storytelling engages the amygdala and hippocampus, which collaborate to encode memory more deeply when the content evokes relevance or empathy (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2016).

Employees who experience the human impact of decisions instead of memorizing policy language move from compliance to conscience.

Beyond Content Coverage: Designing for Transfer

Backward Design forces a distinction between knowledge acquisition and knowledge transfer. The brain can store vast information, but retrieval depends on context cues. Unless learners practice applying knowledge in realistic settings, they fail to transfer it (Barnett & Ceci, Psychological Bulletin, 2017).

By defining outcomes first, designers can create authentic assessments that mirror the environments where skills will be used. That design choice leverages context-dependent memory: the tendency for recall to improve when the learning and application contexts share cues (Smith & Vela, 2020).

In corporate learning, this might look like virtual simulations or scenario-based branching conversations. In leadership development, it might mean peer coaching circles that mirror real decision dynamics.

Every time a learner practices in context, the brain rehearses the same neural patterns it will later need to perform the task in reality. That rehearsal is the foundation of experience-dependent neuroplasticity.

The Coaching Program That Scaled

A healthcare system wants to scale its internal coaching culture. Early attempts rely on PowerPoint workshops that outline listening skills and questioning techniques. Participants rate sessions as “useful” but show little improvement.

When the team applies Backward Design, they start with a bigger question: What will be different in our organization if coaching truly takes hold?

Their answer: Leaders will spend more time developing people than directing them.

That becomes the north star.

Evidence is defined as observable behavioral change, measured through 360-degree feedback, pulse surveys, and manager reflections.

The learning experiences shift dramatically. Instead of lecture-based sessions, participants observe model conversations, deconstruct what worked, and practice real dialogues in pairs. They record reflections using a digital journal to track cognitive and emotional insights over time.

Research supports this approach. Reflection consolidates learning by re-activating neural traces and integrating emotional and cognitive networks. Feedback, when paired with practice, strengthens the prefrontal-striatal circuits responsible for self-regulation and adaptive decision-making.

By anchoring every design choice in the desired result, leaders who develop others create alignment between organizational goals, pedagogy, and the way the brain naturally learns.

Why Designers Drift Away from Backward Design

Backward Design brings clarity and purpose to learning, yet in fast-paced environments teams often rush straight to content. Centering the process on outcomes first creates courses that feel polished, cognitively aligned, and deeply effective.

Backward Design asks us to slow down at the beginning to accelerate impact later. That initial discipline creates psychological clarity for designers and learners alike. Every piece of content earns its place because it connects to a larger narrative of growth.

From a neuroscience perspective, this approach reduces cognitive load, or the strain on working memory when learners face irrelevant or disorganized material (Sweller et al., 2019). Streamlined design frees mental bandwidth for reasoning, reflection, and integration.

How to Begin Applying Backward Design

Start every project with one “North Star” question:

“What would success look like six months from now if this worked perfectly?”The answer defines your desired result.

Translate the result into evidence.

Ask, “How will we know?”Identify the data, behaviors, or outputs that indicate learning transfer.

Design only what moves learners toward that evidence.

Every story, exercise, or assessment should serve a cognitive purpose, activating prior knowledge, applying skills, or reinforcing reflection.

Build in retrieval and reflection loops.

Each moment of recall or self-explanation strengthens the brain’s retrieval pathways (Karpicke & Blunt, 2019).

Tell the learner why it matters.

Relevance activates emotion, and emotion drives retention.

Backward Design is a liberating approach that gives creativity direction and purpose. With a clear end in mind, ideas flow freely and design becomes more intentional and impactful.

Reflection

What outcome are you currently designing toward that feels fuzzy or undefined?

How might reframing it through Backward Design clarify the “why” for both you and the learner?

What evidence would convince you that real learning—not just participation—occurred?

Design guided by the end in mind creates learning that extends beyond knowledge, cultivating insight, application, and meaningful growth.

The Larger Lesson

Backward Design bridges theory, neuroscience, and humanity. It honors how the brain learns: through purpose, feedback, and context, and how people grow: through relevance, agency, and connection.

In every setting, from classrooms to corporate boardrooms, backward design reminds us that learning begins with the future we hope to create.