What Election Day Teaches Us About Action Mapping

Every Election Day, millions of people engage in one of the most behavior-based systems on earth. Voters line up, follow a sequence of procedures, and perform a precise series of actions that determine outcomes far beyond their individual control.

The outcome depends less on what voters know about voting and more on the actions they choose to take, and that’s the very essence of Action Mapping in instructional design!

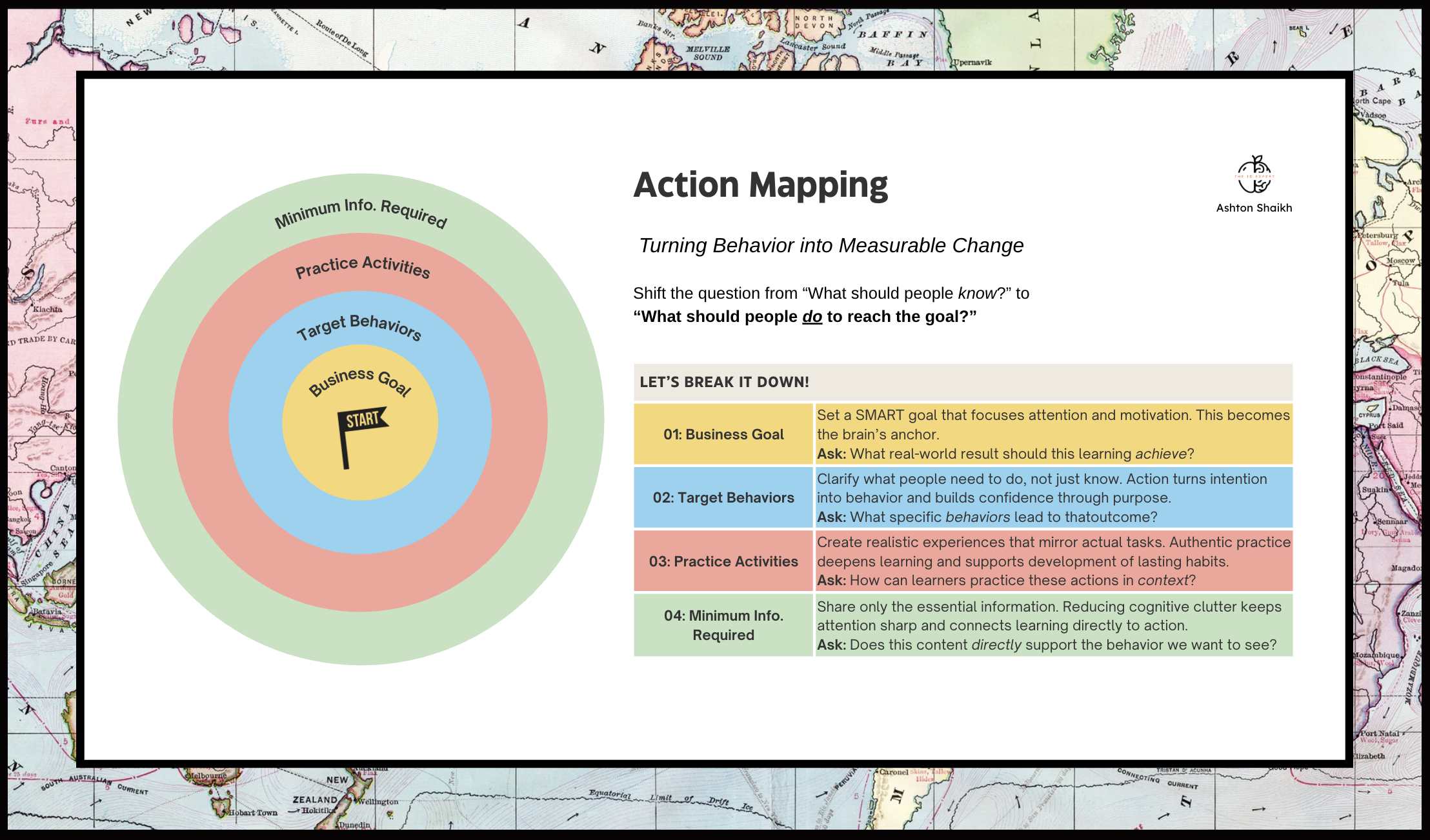

Cathy Moore’s model begins with a simple but transformative question:

“What do people need to do, not just know, to reach the goal?”

The same principle that powers democracy also powers effective learning design. Elections run on behavior rather than belief, and instructional design should, too.

From Information to Action

Picture a training session filled with slides, like dense text, polished graphics, and an impressive facilitator guide. The intention is good: inform, inspire, enlighten. Yet, after the session, performance in the real world looks the same. People know more, but they don’t do more.

That gap between knowing and doing mirrors the gap between civic knowledge and civic action. A person may understand every candidate’s platform yet still skip voting day. Information alone doesn’t move behavior.

Action Mapping closes that gap by stripping design down to what matters most: the behaviors that drive results. It removes the clutter that distracts the brain from application and focuses attention on performance in context.

Step 1: Define the Goal

On Election Day, no one is confused about the goal. Every sign, instruction, and ballot leads to one clear outcome: casting a valid vote.

Effective learning design starts the same way. Define a single, measurable goal that links directly to organizational results. Avoid “awareness” or “understanding” statements. The brain cannot aim at an abstraction.

Neuroscience shows that clear goals activate the brain’s reward systems, improving focus and persistence (Berkman, 2017). Vague goals, by contrast, disperse attention.

For example:

“By the end of training, team leads will conduct three peer reviews per week, reducing rework by 20% next quarter.”

That statement gives the brain a visible target. It clarifies purpose, relevance, and success criteria, all in one line.

Step 2: Identify the Actions that Drive the Goal

Before voters step into the polling station, they know exactly what to do: verify identity, complete the ballot, submit it correctly. Each action connects to the overall outcome.

Once a learning goal is defined, the next question is:

“What specific actions must people take to reach this goal?”

If the goal is reducing rework errors, key actions might include:

Cross-checking deliverables.

Logging feedback in a shared tracker.

Reviewing data sources before submission.

When designers map these behaviors first, content creation becomes strategic. The brain thrives on action-oriented clarity, constructing a mental roadmap that links intention to execution (Carew & Soderstrom, 2019).

Step 3: Design Practice that Mirrors Reality

Election systems teach democracy by empowering people to learn through action. Ballot marking, verification, submission are all practiced and repeated.

Training should do the same. Instead of explaining processes in theory, simulate them. Replace the slide that says “Peer review is important” with an actual review scenario. Ask learners to practice giving feedback, flagging issues, or completing a checklist under realistic conditions.

Soderstrom and Bjork (2015) found that practice grounded in authentic context produces stronger retention and transfer. The brain builds neural efficiency when the learning environment resembles the real one.

Knowledge grows stronger when it’s applied, turning insight into lasting skill.

Step 4: Provide Just Enough Information

Voters don’t receive a 50-page manual before voting. They see concise signage, guided pathways, and minimal instructions, only what’s required to complete the process successfully.

In Action Mapping, information supports behavior rather than driving it. Each piece of content should serve a clear purpose: “Does this help learners perform the target action?” If not, go ahead and remove it.

Daniel Willingham (2020) emphasizes that working memory is finite; overload disrupts comprehension. Cognitive clarity, what neuroscientists call signal over noise, ensures learning moves from awareness to action.

Less content often leads to more learning because the brain has space to focus on doing.

Step 5: Build Feedback Loops that Strengthen Learning

Elections rely on feedback, such as voter confirmations, audit systems, recounts. Feedback ensures accuracy and integrity.

Learning depends on it, too. The brain’s reward systems activate when performance is acknowledged and guided (Berkman et al., 2017). The key is specificity.

Replace “Good job” with:

“You caught a data error early, excellent observation! Next time, try double-check source formatting to save even more time.”

Such feedback connects effort to progress, reinforcing neural pathways for performance. Learners feel seen, supported, and motivated.

Feedback works best when it’s woven into the process, turning practice into growth and learning into lasting improvement.

Step 6: Measure What Matters

Elections measure success through counted ballots instead of enthusiasm surveys, and learning should be evaluated the same way.

Training success shouldn’t hinge on completion rates or participant satisfaction. It should measure behavior change aligned to the original goal: fewer rework errors, faster customer resolution, better safety compliance.

When learners can see measurable progress, the brain’s reward circuitry strengthens engagement (Willingham, 2020). Metrics matter because they make growth visible, and visibility builds motivation!

Step 7: Support Transfer Beyond the “Polling Booth”

Civic participation doesn’t end when a ballot is cast. It continues through reflection, conversation, and planning for the next election cycle.

The same is true for learning transfer. Real performance change happens after the session ends, when learners apply new behaviors in daily work.

Reflection prompts, follow-up coaching, and short refreshers reinforce memory consolidation and identity integration (Damasio, 2021). Action Mapping extends beyond delivery, building in reinforcement to ensure lasting transfer.

The ultimate goal goes beyond compliance, focusing on developing competence that endures and continues to grow over time.

The Brain Behind Action Mapping

Action Mapping aligns naturally with how the brain learns:

Action drives attention and encoding.

Feedback strengthens synaptic pathways.

Clarity organizes motivation and effort.

Immordino-Yang (2016) reminds us that emotion and cognition are inseparable. Learners act when relevance feels personal. Moore’s model honors that by placing human action, like real decisions, meaningful tasks, at the center of design.

Action Mapping represents more than a checklist, which is a genuine shift in mindset that transforms learning from passive intake to purposeful, active engagement.

Election Day: The Perfect Mirror for Design Choices

The structure of Election Day is pure Action Mapping in motion:

Goal: In an election, the goal is to cast a valid ballot, a clear, measurable outcome. In design, this mirrors the process of defining what success looks like and ensuring learners know the target they’re working toward.

Actions: Voters verify their identity, mark their ballot, and submit it. Similarly, designers identify the key behaviors that demonstrate learning and lead to the desired outcome.

Practice: Before Election Day, voters might use sample ballots or voter education materials to build confidence. In learning design, this is about creating contextual practice that mirrors real decisions and situations.

Feedback: When voters receive a confirmation slip, it provides instant assurance that their effort counted. Designers can replicate this through immediate, specific feedback that reinforces accuracy and motivation.

Measurement: Ballots are counted to determine results, just as assessments measure real performance, not just recall or participation.

Transfer: Finally, ongoing civic engagement represents transfer, which is when knowledge and skills continue to shape behavior long after the learning experience ends.

Every element serves the final outcome. Nothing exists for its own sake. Training design should function the same way: lean, intentional, and grounded in action.

Why This Matters

Modern workplaces succeed through meaningful transformation fueled by purposeful learning. Employees already hold a wealth of knowledge, and their potential grows when they’re given clear cues, supportive context, and opportunities to act with intention.

Action Mapping honors cognitive limits while amplifying human potential. It respects attention as a finite resource and aligns design with neuroscience: purpose, relevance, and feedback.

When learning is designed this way, people move beyond attendance and into meaningful action. Behavior becomes the catalyst for growth, driving real progress across the organization.

Reflection

Before building your next training program, pause and ask:

What business problem am I solving?

What do people need to do to solve it?

How can I let them practice those actions in ways that feel psychologically safe, supportive, and genuinely meaningful?

If the answer leads to fewer slides and more simulation, fewer facts and more feedback, you’re on the right path!

The brain remembers best through experience, and learning deepens when knowledge is put into action.

Final Thought

Election Day reminds us that clarity and structure can empower millions of people to take action confidently and independently. Learning design works the same way.

When you lead with behavior, you create alignment between cognition and purpose.

When you measure action, you prove impact.

And when you design for doing, rather than just knowing, learning becomes a form of participation, one that shapes both people and systems.

Action Mapping represents more than a model, serving as a reminder that knowledge finds its true power through action that creates meaningful change.